🙅♂️ The Reasons Why Investors Say "No" (Pre-Seed to Series C)

The founder's guide on how to de-risk your startup to investors.

👋 Hey, Chris here! Welcome to BrainDumps—a weekly series from The Founders Corner. If you’ve been reading along, you know this series is a preview of a bigger project. Well, it’s finally here: The Big Book of BrainDumps is out now!

It isn’t a theory book—it’s the founder’s field manual. Inside, you’ll find 70 powerful frameworks distilled from 30+ years scaling software companies to hundreds of millions in ARR, 20+ years investing in 500+ B2B tech startups, and over $1B of shareholder value created. From raising capital to hiring your first VP of Sales, this book turns scars and successes into practical playbooks you’ll return to again and again. I expect most copies will become well-worn, scribbled on, and dog-eared—because it works.

Table of Contents

Pre-Seed: Prove You Can Build It (Technical Risk)

Seed: Prove It Solves a Pain (Market Risk)

Series A: Prove You Can Sell It Repeatedly (GTM Risk)

Series B: Prove You Can Scale It Efficiently (TAM + Model Risk)

Series C and Beyond: Prove Your Culture Can Withstand Scale (People Risk)

Why This Matters: You’re Not Just Building a Business. You’re Eliminating Excuses.

Final Words: Think Like an Investor. Act Like a Builder.

Here’s the truth they don’t tell you about fundraising:

You’re not raising money.

You’re removing reasons for investors to say no.

That’s the game.

Each funding round isn’t just a new level of capital. It’s a new level of risk that needs to be de-risked. Cleanly. Systematically. Convincingly.

I can’t tell you how many founders I’ve met who built a great product, showed decent traction… and still struggled to raise. Not because they weren’t smart. Not because the opportunity wasn’t real.

But because they hadn’t tackled the right risks at the right time.

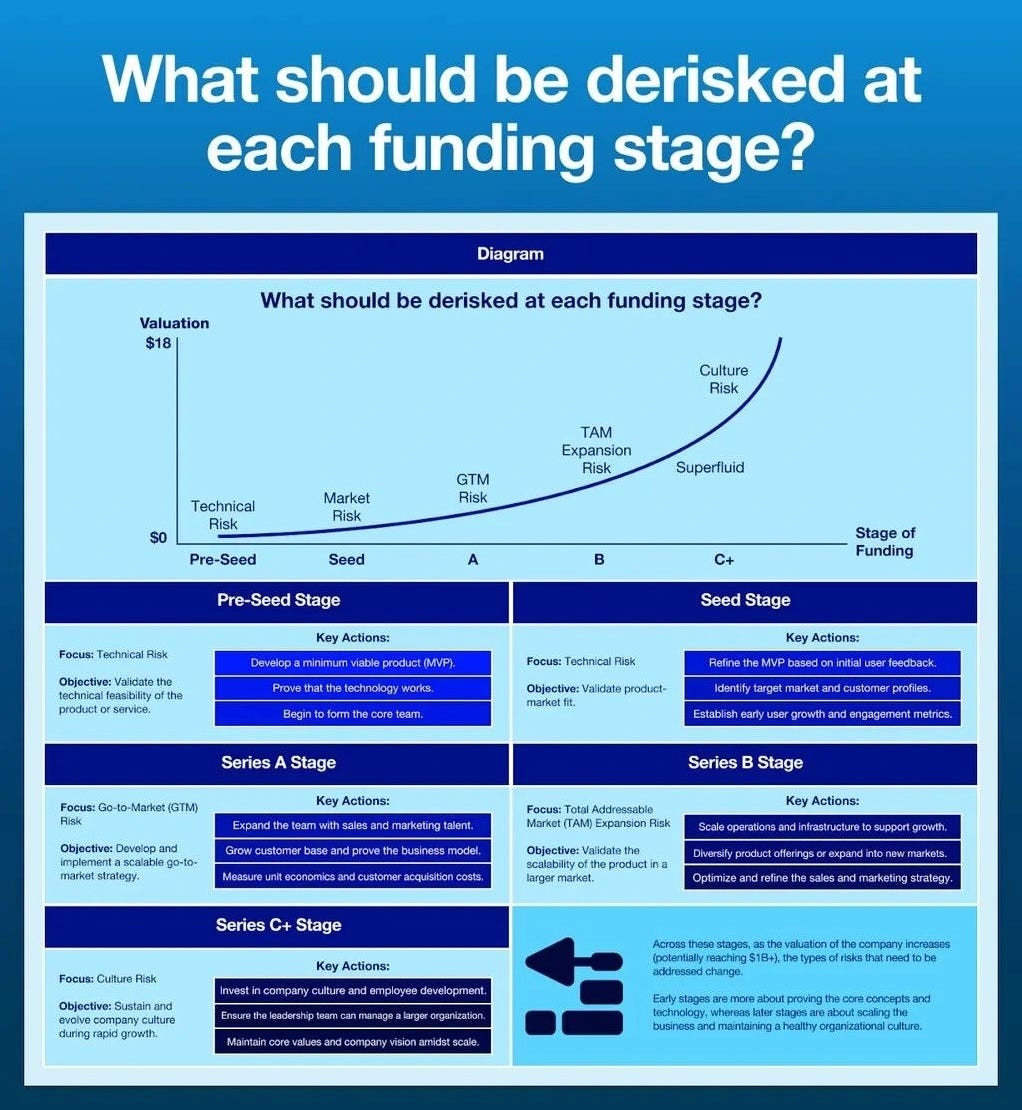

So when I saw this visual BrainDump—courtesy of Abhishek Maran and the team at Superfluid—I thought: finally, someone mapped it. A clear, stage-by-stage breakdown of what needs to be de-risked, when, and why.

Let’s unpack it, founder-style.

Pre-Seed: Prove You Can Build It (Technical Risk)

At this stage, you're raising belief capital. No revenue, no customers, no proof. Just a strong conviction—and a fragile prototype.

The Biggest Risk:

Your idea sounds great… but can you build it?

You need to show investors (and yourself) that this isn’t just vaporware. That your MVP isn’t just a prototype—it’s the proof point that the product works and that you can build it faster, cheaper, and smarter than anyone else.

Your job is to de-risk technical feasibility.

Key Actions:

Build a functioning MVP (not a landing page, a working product).

Get your first 5–10 users—even if they’re not paying.

Prove that the technology solves a real, specific problem.

Personal Take:

When I backed a devtools startup in this phase, they had zero revenue. But they showed me a CLI tool with 50 developers using it weekly—and they could demo real-time results. That was enough.

Seed: Prove It Solves a Pain (Market Risk)

Now that the thing works, the question changes: does anyone care?

This is the land of product-market fit hunting. You’re not scaling yet. You’re still listening. Tinkering. Validating.

The Biggest Risk:

You’ve built something technically sound… but is there a real market that needs this now?

Your job is to de-risk market risk.

Key Actions:

Show active usage and strong engagement (DAUs/WAUs, retention).

Collect customer testimonials and pain-point quotes.

Prove that someone will pay for it (even small amounts count).

Personal Take:

At this stage, I’m not looking for a polished revenue engine. I’m looking for evidence of love—strong pull from a specific user base. One founder I backed had just 20 customers but a 90% activation rate and 100% month-on-month retention. No brainer.

Series A: Prove You Can Sell It Repeatedly (GTM Risk)

Now you’ve got product-market fit. You’ve figured out what to sell. The next question is how you sell it—and whether that model scales.

Welcome to go-to-market hell (and heaven, if you get it right).

The Biggest Risk:

You’ve got early traction—but can you acquire and retain customers efficiently and repeatably?

This is where most companies fall into the “Series A Crunch.” The story shifts from product to performance.

Your job is to de-risk go-to-market execution.

Key Actions:

Prove you have one repeatable acquisition channel (outbound, content, PLG, etc.).

Show your CAC and LTV numbers—and that they’re moving in the right direction.

Build a proper funnel: top, middle, conversion, retention.

Personal Take:

No one wants to fund chaos. If you’re still flailing between strategies, you’re not ready for Series A. Show me a sales playbook. Show me conversion data. Show me how you’ll go from 50 customers to 500.

Series B: Prove You Can Scale It Efficiently (TAM + Model Risk)

Series B is where the stakes rise. You’ve proven your product. You’ve proven your GTM engine. Now the question is: Can this become a really big company?

The Biggest Risk:

You’ve found a wedge… but is the market big enough? Is your model adaptable enough?

Your job is to de-risk scalability and market ceiling.

Key Actions:

Expand your total addressable market (new personas, verticals, or geographies).

Introduce new revenue streams or upsell paths.

Build an executive team to handle functional complexity.

Implement operational systems (CRM, CS, finance stack).

Personal Take:

At this stage, we expect operational maturity. You’re no longer “figuring things out”—you’re fine-tuning what already works. Show us that every dollar in can turn into five out. And show us you can handle growth without chaos.

Series C and Beyond: Prove Your Culture Can Withstand Scale (People Risk)

You’re now a serious business. Growth is predictable. Your model works. Your market is validated.

So what could go wrong?

The Biggest Risk:

The culture collapses. Politics creeps in. Talent leaves. The company drifts.

At this scale, people risk becomes the silent killer.

Your job is to de-risk culture and alignment.

Key Actions:

Define and communicate your values clearly.

Build systems for feedback, goal-setting, and recognition.

Retain key leadership and nurture future leaders.

Codify the mission, vision, and rhythm of the business.

Personal Take:

One startup I advised went from 80 to 300 employees in 18 months post-Series C. ARR doubled… but culture nosedived. The founder was in back-to-back board meetings and lost touch with the team. Burnout exploded. Talent fled. Valuation halved.

Culture doesn’t just “scale.” You have to build it for scale.

Why This Matters: You’re Not Just Building a Business. You’re Eliminating Excuses.

Let’s be blunt.

Investors don’t back perfect businesses.

They back founders who understand their risks—and have a plan to remove them.

This is what makes this BrainDump so valuable. It reframes fundraising from “how much can I raise?” to “what’s stopping me from being investable?”

Each stage has its own trapdoor:

At Pre-Seed, it’s “Can you build it?”

At Seed, it’s “Will anyone pay for it?”

At Series A, it’s “Can you sell it repeatably?”

At Series B, it’s “Can this become huge?”

At Series C, it’s “Can your people sustain this?”

De-risking each of these systematically is how you win. It’s how you raise. It’s how you build something that lasts.

Final Words: Think Like an Investor. Act Like a Builder.

If you take nothing else from this post, take this:

Every funding round is a conversation about risk.

The better you understand yours…

The faster you eliminate them…

The more confident investors will feel giving you capital.

Because great founders don’t just tell a compelling story.

They remove every reason not to believe it.

—Chris Tottman

I would challenge the notion that the risk we address at the pre-seed is the one of feasibility (whether a startup can build it).

Sitting on the engineering side for 25 straight years, I am officially biased :) but I'd argue that the default answer is that you almost certainly can build it.

And building it, they are. Often with no traction whatsoever. The missing part was either problem-solution fit or product-market fit. Or a combination of the two.

I often use the model of:

0. Ideation/Dream

1. Problem-Solution Fit

2. Product-Market Fit

3. Growth

In reality, though, it is a big oversimplification. While the accents change, the first three steps overlap each other. A successful problem-solution fit, followed by an unsuccessful (or, more likely, an unsuccessful enough) product-market fit, sends founders back somewhere between ideation and the problem-solution fit.

Technical feasibility is just another dimension at these early stages. It's rarely a function of whether it can be built (it can), but rather how much it would cost to build it (probably too much), which sends founders back to the earlier stages to ideate something more affordable.

The assessment of the earliest stages of development, thus, will always lie at the intersection of the three:

- whether we're solving a problem customers care about (problem space)

- whether our solution at least promises business viability (go-to-market space)

- what's the minimal thing that may validate the assumptions above (technical space)

Great write-up, Chris! The overview of the different phases and the key obstacles to overcome in each is really helpful. I found this comment particularly interesting: Culture doesn’t just “scale.” You have to build it for scale.

Would love to hear more on this at some point, and what best practice in this space might look like.